Our March 18th Technology Salon NYC covered the Internet of Things and Global Development with three experienced discussants: John Garrity, Global Technology Policy Advisor at CISCO and co-author of Harnessing the Internet of Things for Global Development; Sylvia Cadena, Community Partnerships Specialist, Asia Pacific Network Information Centre (APNIC) and the Asia Information Society Innovation Fund (ISIF); and Andy McWilliams, Creative Technologist at ThoughtWorks and founder and director of Art-A-Hack and Hardware Hack Lab.

What is the Internet of Things?

One key task at the Salon was clarifying what exactly is the “Internet of Things.” According to Wikipedia:

The Internet of Things (IoT) is the network of physical objects—devices, vehicles, buildings and other items—embedded with electronics, software, sensors, and network connectivity that enables these objects to collect and exchange data.[1] The IoT allows objects to be sensed and controlled remotely across existing network infrastructure,[2] creating opportunities for more direct integration of the physical world into computer-based systems, and resulting in improved efficiency, accuracy and economic benefit;[3][4][5][6][7][8] when IoT is augmented with sensors and actuators, the technology becomes an instance of the more general class of cyber-physical systems, which also encompasses technologies such as smart grids, smart homes, intelligent transportation and smart cities. Each thing is uniquely identifiable through its embedded computing system but is able to interoperate within the existing Internet infrastructure. Experts estimate that the IoT will consist of almost 50 billion objects by 2020.[9]

As one discussant explained, the IoT involves three categories of entities: sensors, actuators and computing devices. Sensors read data in from the world for computing devices to process via a decision logic which then generates some type of action back out to the world (motors that turn doors, control systems that operate water pumps, actions happening through a touch screen, etc.). Sensors can be anything from video cameras to thermometers or humidity sensors. They can be consumer items (like a garage door opener or a wearable device) or industrial grade (like those that keep giant machinery running in an oil field). Sensors are common in mobile phones, but more and more we see them being de-coupled from cell phones and integrated into or attached to all manner of other every day things. The boom in the IoT means that in whereas in the past, a person may have had one URL for their desktop computer, now they might be occupying several URLs: through their phone, their iPad, their laptop, their Fitbit and a number of other ‘things.’

Why does IoT matter for Global Development?

Price points for sensors are going down very quickly and wireless networks are steadily expanding — not just wifi but macro cellular technologies. According to one lead discussant, 95% of the world is covered by 2G and two-thirds by 3G networks. Alongside that is a plethora of technology that is wide range and low tech. This means that all kinds of data, all over the world, are going to be available in massive quantities through the IoT. Some are excited about this because of how data can be used to track global development indicators, for example, the type of data being sought to measure the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Others are concerned about the impact of data collected via the IoT on privacy.

What are some examples of the IoT in Global Development?

Discussants and others gave many examples of how the IoT is making its way into development initiatives, including:

- Flow meters and water sensors to track whether hand pumps are working

- Protecting the vaccine cold chain – with a 2G thermometer, an individual can monitor the cold chain for local use and the information also goes directly to health ministries and to donors

- Monitoring the environment and tracking animals or endangered species

- Monitoring traffic routes to manage traffic systems

- Managing micro-irrigation of small shareholder plots from a distance through a feature phone

- As a complement to traditional monitoring and evaluation (M&E) — a sensor on a cook stove can track how often a stove is actually used (versus information an individual might provide using recall), helping to corroborate and reduce bias

- Verifying whether a teacher is teaching or has shown up to school using a video camera

The CISCO publication on the IoT and Global Development provides many more examples and an overview of where the area is now and where it’s heading.

How advanced is the IoT in the development space?

Currently, IoT in global development is very much a hacker space, according to one discussant. There are very few off the shelf solutions that development or humanitarian organizations can purchase and readily implement. Some social enterprises are ramping up activity, but there is no larger ecosystem of opportunities for off the shelf products.

Because the IoT in global development is at an early phase, challenges abound. Technical issues, power requirements, reliability and upkeep of sensors (which need to be calibrated), IP issues, security and privacy, technical capacity, and policy questions all need to be worked out. One discussant noted that these challenges carry on from the mobile for development (m4d) and information and communication technologies for development (ICT4D) work of the past.

Participants agreed that challenges are currently huge. For example, devices are homogeneous, making them very easy to hack and affect a lot of devices at once. No one has completely gotten their head around the privacy and consent issues, which are are very different than those of using FB. There are lots of interoperability issues also. As one person highlighted — there are over 100 different communication protocols being used today. It is more complicated than the old “BetaMax v VHS” question – we have no idea at this point what the standard will be for IoT.

For those who see the IoT as a follow-on from ICT4D and m4d, the big question is how to make sure we are applying what we’ve learned and avoiding the same mistakes and pitfalls. “We need to be sure we’re not committing the error of just seeing the next big thing, the next shiny device, and forgetting what we already know,” said one discussant. There is plenty of material and documentation on how to avoid repeating past mistakes, he noted. “Read ICT works. Avoid pilotitis. Don’t be tech-led. Use open source and so on…. Look at the digital principles and apply them to the IoT.”

A higher level question, as one person commented, is around the “inconvenient truth” that although ICTs drive economic growth at the macro level, they also drive income inequality. No one knows how the IoT will contribute or create harm on that front.

Are there any existing standards for the IoT? Should there be?

Because there is so much going on with the IoT – new interventions, different sectors, all kinds of devices, a huge variety in levels of use, from hacker spaces up to industrial applications — there are a huge range of standards and protocols out there, said one discussant. “We don’t really want to see governments picking winners or saying ‘we’re going to us this or that.’ We want to see the market play out and the better protocols to bubble up to the surface. What’s working best where? What’s cost effective? What open protocols might be most useful?”

Another discussant pointed out that there is a legacy predating the IOT: machine-to-machine (M2M), which has not always been Internet based. “Since this legacy is still there. How can we move things forward with regard to standardization and interoperability yet also avoid leaving out those who are using M2M?”

What’s up with IPv4 and IPv6 and the IoT? (And why haven’t I heard about this?)

Another crucial technical point raised is that of IPv4 and IPv6, something that not many Salon participant had heard of, but that will greatly impact on how the IoT rolls out and expands, and just who will be left out of this new digital divide. (Note: I found this video to be helpful for explaining IPv4 vs IPv6.)

“Remember when we used Netscape and we understood how an IP number translated into an IP address…?” asked one discussant. “Many people never get that lovely experience these days, but it’s important! There is a finite number of IP4 addresses and they are running out. Only Africa and Latin America have addresses left,” she noted.

IPv6 has been around for 20 years but there has not been a serious effort to switch over. Yet in order to connect the next billion and the multiple devices that they may bring online, we need more addresses. “Your laptop, your mobile, your coffee pot, your fridge, your TV – for many of us these are all now connected devices. One person might be using 10 IP addresses. Multiply that by millions of people, and the only thing that makes sense is switching over to IPv6,” she said.

There is a problem with the technical skills and the political decisions needed to make that transition happen. For much of the world, the IoT will not happen very smoothly and entire regions may be left out of the IoT revolution if high level decision makers don’t decide to move ahead with IPv6.

What are some of the other challenges with global roll-out of IoT?

In addition to the IPv4 – IPv6 transition, there are all kinds of other challenges with the IoT, noted one discussant. The technical skills required to make the transition that would enable IoT in some regions, for example Asia Pacific, are sorely needed. Engineers will need to understand how to make this shift happen, and in some places that is going to be a big challenge. “Things have always been connected to the Internet. There are just going to be lots more, different things connected to the Internet now.”

One major challenge is that there are huge ethical questions along with security and connectivity holes (as I will outline later in this summary post, and as discussed in last year’s salon on Wearable Technologies). In addition, noted one discussant, if we are designing networks that are going to collect data for diseases, for vaccines, for all kinds of normal businesses, and put the data in the cloud, developing countries need to have the ability to secure the data, the computing capacity to deal with it, and the skills to do their own data analysis.

“By pushing the IoT onto countries and not supporting the capacity to manage it, instead of helping with development, you are again creating a giant gap. There will be all kinds of data collected on climate change in the Pacific Island Countries, for example, but the countries don’t have capacity to deal with this data. So once more it will be a bunch of outsiders coming in to tell the Pacific Islands how to manage it, all based on conclusions that outsiders are making based on sensor data with no context,” alerted one discussant. “Instead, we should be counseling our people, our countries to figure out what they want to do with these sensors and with this data and asking them what they need to strengthen their own capacities.”

“This is not for the SDGs and ticking off boxes,” she noted. “We need to get people on the ground involved. We need to decentralize this so that people can make their own decisions and manage their own knowledge. This is where the real empowerment is – where local people and country leaders know how to collect data and use it to make their own decisions. The thing here is ownership — deploying your own infrastructure and knowing what to do with it.”

How can we balance the shiny devices with the necessary capacities?

Although the critical need to invest in and support country-level capacity to manage the IoT has been raised, this type of back-end work is always much less ‘sexy’ and less interesting for donors than measuring some development programming with a flashy sensor. “No one wants to fund this capacity strengthening,” said one discussant. “Everyone just wants to fund the shiny sensors. This chase after innovation is really damaging the impact that technology can actually have. No one just lets things sit and develop — to rest and brew — instead we see everyone rushing onto the next big thing. This is not a good thing for a small country that doesn’t have the capacity to jump right into it.”

All kinds of things can go wrong if people are not trained on how to manage the IoT. Devices can be hacked and they may be collecting and sharing data without an individuals’ knowledge (see Geoff Huston on The Internet of Stupid Things). Electrical short outs, common in places with poor electricity ecosystems, can also cause big problems. In addition, the Internet is affected by legacy systems – so we need interoperability that goes backwards, said one discussant. “If we don’t make at least a small effort to respect those legacy systems, we’re basically saying ‘if you don’t have the funding to update your system, you’re out.’ This then reinforces a power dynamic where countries need the international community to give them equipment, or they need to buy this or buy that, and to bring in international experts from the outside….’ The pressure on poor countries to make things work, to do new kinds of M&E, to provide evidence is huge. With that pressure comes a higher risk of falling behind very quickly. We are also seeing pilot projects that were working just fine without fancy tech being replaced by new fangled tech-type programs instead of being supported over the longer term,” she said.

Others agreed that the development sector’s fascination with shiny and new is detrimental. “There is very little concern for the long-term, the legacy system, future upgrades,” said one participant. “Once the blog post goes up about the cool project, the sensors go bad or stop working and no one even knows because people have moved on.” Another agreed, citing that when visiting numerous clinics for a health monitoring program in one country, the running joke among the M&E staff was “OK, now let’s go and find the broken solar panel.” “When I think of the IoT,” she said, “I think of a lot of broken devices in 5 years.” The aspect of eWaste and the IoT has not even begun to be examined or quantified, noted another.

It is increasingly important for governments to understand how the Internet works, because they are making policy about it. Manufacturers need to better understand how the tech works on the ground, especially in different contexts that they are not accustomed to working in. Users need a better understanding of all of this because their privacy is at risk. Legal frameworks around data and national laws need more attention as well. “When you are working with restrictive governments, your organization’s or start-up’s idea might actually be illegal or close to a sedition law and you may end up in jail,” noted one discussant.

What choices will organizations need to make regarding the IoT?

When it comes to actually making decisions on how involved an organization should and can be in supporting or using the IoT, one critical choice will be related the suites of devices, said our third discussant. Will it be a cloud device? A local computing device? A computer?

Organizations will need to decide if they want a vendor that gives them a package, or if they want a modular, interoperable approach of units. They will need to think about aspects like whether they want to go with proprietary or open source and will it be plug and play?

There are trade-offs here and key technical infrastructure choices will need to be made based on a certain level of expertise and experience. If organizations are not sure what they need, they may wish to get some advice before setting up a system or investing heavily.

As one discussant put it, “When I talk about the IOT, I often say to think about what the Internet was in the 90s. Think about that hazy idea we had of what the Internet was going to be. We couldn’t have predicted in the 90s what today’s internet would look like, and we’re in the same place with the IoT,” he said. “There will be seismic change. The state of the whole sector is immature now. There are very hard choices to make.”

Another aspect that’s representative of the IoT’s early stage, he noted, is that the discussion is all focusing on http and the Internet. “The IOT doesn’t necessarily even have to involve the Internet,” he said.

Most vendors are offering a solution with sensors to deploy, actuators to control and a cloud service where you log in to find your data. The default model is that the decision logic takes place there in the cloud, where data is stored. In this model, the cloud is in the middle, and the devices are around it, he said, but the model does not have to be that way.

Other models can offer more privacy to users, he said. “When you think of privacy and security – the healthcare maxim is ‘do no harm.’ However this current, familiar model for the IoT might actually be malicious.” The reason that the central node in the commercial model is the cloud is because companies can get more and more detailed information on what people are doing. IoT vendors and IoT companies are interested in extending their profiles of people. Data on what people do in their virtual life can now be combined with what they do in their private lives, and this has huge commercial value.

One option to look at, he shared, is a model that has a local connectivity component. This can be something like bluetooth mesh, for example. In this way, the connectivity doesn’t have to go to the cloud or the Internet at all. This kind of set-up may make more sense with local data, and it can also help with local ownership, he said. Everything that happens in the cloud in the commercial model can actually happen on a local hub or device that opens just for the community of users. In this case, you don’t have to share the data with the world. Although this type of a model requires greater local tech capacity and can have the drawback that it is more difficult to push out software updates, it’s an option that may help to enhance local ownership and privacy.

This requires a ‘person first’ concept of design. “When you are designing IOT systems, he said, “start with the value you are trying to create for individuals or organizations on the ground. And then implement the local part that you need to give local value. Then, only if needed, do you add on additional layers of the onion of connectivity, depending on the project.” The first priority here are the goals that the technology design will achieve for individual value, for an individual client or community, not for commercial use of people’s data.

Another point that this discussant highlighted was the need to conduct threat modeling and to think about unintended consequences. “If someone hacked this data – what could go wrong?” He suggested working backwards and thinking: “What should I take offline? How do I protect it better? How do I anonymize it better.”

In conclusion….

It’s critical to understand the purpose of an IoT project or initiative, discussants agreed, to understand if and why scale is needed, and to be clear about the drivers of a project. In some cases, the cloud is desirable for quicker, easier set up and updates to software. At the same time, if an initiative is going to be sustainable, then community and/or country capacity to run it, sustain it, keep it protected and private, and benefit from it needs to be built in. A big part of that capacity includes the ability to understand the different layers that surround the IoT and to make grounded decisions on the various trade-offs that will come to a head in the process of design and implementation. These skills and capacities need to be developed and supported within communities, countries and organizations if the IoT is to contribute ethically and robustly to global development.

—

Thanks to APNIC for sponsoring and supporting this Salon and to our friends at ThoughtWorks for hosting! If you’d like to join discussions like this one in cities around the world, sign up at Technology Salon.

Salons are held under Chatham House Rule, therefore no attribution has been made in this post.

Read Full Post »

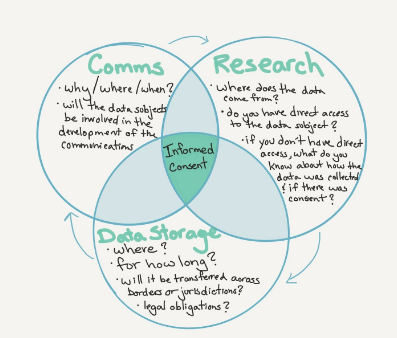

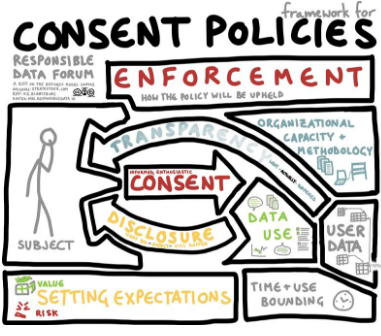

ything else. We often start from the point of collection when really it’s at the design stage when we should think about the burden of data collection and define what’s the minimum we can ask of people? How we design – even how we get consent – can inform how the whole process happens.

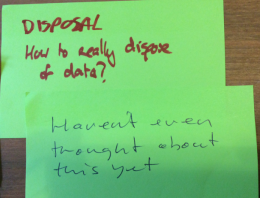

ything else. We often start from the point of collection when really it’s at the design stage when we should think about the burden of data collection and define what’s the minimum we can ask of people? How we design – even how we get consent – can inform how the whole process happens. It’s difficult to dispose of data when there are multiple versions of it and a data footprint.

It’s difficult to dispose of data when there are multiple versions of it and a data footprint. At our April 5th Salon in Washington, DC we had the opportunity to take a closer look at

At our April 5th Salon in Washington, DC we had the opportunity to take a closer look at

Our December 2015 Technology Salon discussion in NYC focused on

Our December 2015 Technology Salon discussion in NYC focused on