Mapping Violence against Children in Benin

In my last post, I wrote about key questions to ask before adding ICTs to a development initiative, using the example of a violence against children program I’m working on in Benin. The piece that was missing, and which came together over the past 2 weeks, was the view from the ground.

We just finished two workshops (in Natitingou and Couffo Districts) with 24 youth from 9-10 villages in each district, the district heads of the Center for Social Protection (CPS), and the Ministry of the Family (both of whom are responsible for responding to cases of child abuse/child rights violations in their varying forms). We covered several topics related to youth leadership and youth-led advocacy.

I was most excited, though, about getting end user input and thoughts about implementing a FrontlineSMS and Ushahidi set-up as a way of reporting, tracking and responding to violence against children.

I had a lot of questions before arriving to Benin, but by the end of my 2 weeks here, I feel satisfied that the system can work, that it’s reflective of real information and communication flows on the ground, that roles of the different actors – including youth – are clear, that it can add value to local structures and initiatives, and that it could be sustainable and potentially scaled into a national level system in Benin and possibly other countries.

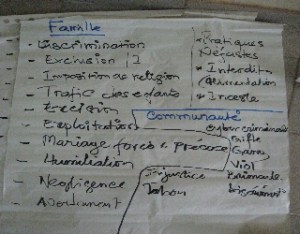

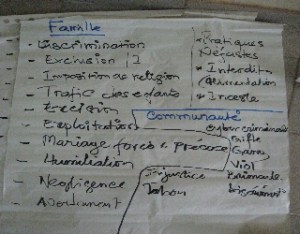

What we are tracking.

Forms of violence that children and youth experience at home and in the community.

The UN Report on Violence against Children (VAC) identified 4 key forms of violence against children (physical, psychological, sexual and neglect) and 5 key places where it takes place (home, school, community, institutions, workplace). Plan is one of the organizations that participated in the elaboration of the study. Now, together with local, national and global partners, we are working on sharing the study’s results and strengthening capacities at different levels to prevent and respond to violence against children.

Plan’s approach helps rights holders (in this case children and youth) know their rights and engages them in educating on and advocating for those rights. At the same time Plan works to strengthen the capacities of duty bearers (local and national institutions, including the family) to ensure those rights.

The VAC study revealed some shocking statistics on violence against children, yet we also know that under-reporting is a reality, meaning that the magnitude of violence is not fully known. People don’t report violence for many reasons, including fear of reprisal and stigma, difficulties in communication and access to places where they could report. Institutions also face difficulties in responding to violence for a variety of reasons, including lack of political will, disinterest, lack of awareness on the magnitude of the problem, scarce resources, poorly functioning or corrupt systems, and poor quality information. Even when violence against children is reported, national response and judicial systems in many countries don’t do a good job of addressing it.

How ICTs can help.

Watching testimonials youth produced during the workshop.

Mobiles can pull in and send out multiple bits of information, creating a kind of glue that can hold a system together. In Benin, the use of SMS and mapping can bolster and connect the existing system for reporting and responding to cases of violence against children. SMS allows for anonymous and low cost reporting. It’s hoped that this will encourage more reporting. More reporting will allow for more information, and for patterns and degrees of violence to be mapped. This in turn can be used to raise awareness around the severity of the problem, advocate for the necessary resources to prevent it, and develop better and more targeted response and follow-up mechanisms. Better information can help design better programs. SMS can alert local authorities quickly and help improve response. Mapping is a visual tool that children and youth can use to advocate for an end to cultural practices that allow for violence against them.

In addition to FrontlineSMS and Ushahidi, digital media tools can be used to record audiovisual information that helps qualify the statistics and better understand attitudes towards violence. At the workshops we trained youth to use low cost video cameras, mobile phones and audio recorders to document violence and to take testimonials from other youth and community members. These testimonials can help youth improve and target their messaging to change violent behaviors and can be used to educate in their communities and generate dialogue around violent practices. Testimonials and audiovisual materials also help youth connect with people outside the borders of their communities to share their realities, challenges and accomplishments via the web.

What the system looks like.

My colleague Henri explaining the basics of the system.

We had some ideas and a drawing of what the system might look like that we shared to get across the basic idea of the system and to obtain user feedback on it.

After the workshops, with input from the youth, national and district level Plan child protection staff, community outreach staff, the Center for Social Protection (CPS) and the Ministry of the Family, it ended up looking something like this (forgive my poor artistic talents….)

My low tech attempt at drawing out the system....

For now, the Frontline SMS piece of the system will be managed by Henri (see photo above) at Plan’s Country Office. Plan’s district level child protection staff will administer the Ushahidi system, receiving and approving the SMS reports that are automatically forwarded to Ushahidi from Frontline SMS. Automatic alerts will be set up so that when there is a case reported in a particular community, the Plan staff person who liaises with that community, as well as the CPS point person, and the local police and any other relevant community level persons will be alerted. These authorities will verify the cases and do the follow up (they are already responsible and trained for this role). The goal is for management of the whole system to be handed over to national authorities.

Main challenges we face(d) and ideas for overcoming them.

There were many questions and thoughts from users about the system that need to be worked out (see below). But these are not insurmountable.

Lack of resources to respond to violence at the local and national level is the main challenge seen by the CPS and local Plan staff. It will be easy to report now because there will be a locally available, low cost and fast system. The number of reports will increase. What if we don’t have enough capacity to respond to them? Children and youth may feel discouraged and stop reporting.

Proposed Solution: Plan Benin will continue to work closely with the Ministry of the Family and the CPS during the 6-12 month pilot phase in the Natitingou and Couffo districts. The end goal is that the CPS and Ministry will manage the entire system. The information collected during the pilot phase will be used to advocate for more resources for prevention and response.

Anastasie

Airtime and mobile phone access in order to report incidents was raised as a potential challenge by children and youth in both groups. What if people don’t have credit? Can Plan purchase credit for the participating youth leaders and buy them phones?

Proposed Solution: My amazing colleague Anastasie, who coordinates the program in West Africa, turned around to youth and said, “Hah? Do you honestly think Plan can purchase credit and mobile phones for the entire country of Benin? No! This is not only Plan’s concern. This is not only happening here in one community or one district. This is a problem that we all share, and we all have a responsibility to do something about.” The kids laughed and agreed that anyone could find a way to report by borrowing a phone if necessary or asking an aunt or friend to help them. The youth that we are working with are all part of organized community youth groups, about half of them have mobile phones and all said that their families or neighbors had phones that they could borrow or use. Still, Plan will approach the government and cell phone providers about getting a “green” number that would allow for free SMS violence reporting.

Phones and modems. “Here (at the Nokia Store) we don’t carry the older models, surely you would prefer this nice new one with many cool features and capabilities?” Um, no, actually what we’re looking for is an older, cheaper phone or one of the modems on our list here! We spent quite some time visiting stores and testing modems and phones to find one that worked with FrontlineSMS. Mobile phones are a complex ecology with many factors — phone or modem model and auto-installed programs they come with, SIM cards, etc.–that can trip you up and there is not a lot of standardization across phones or countries, so what works in one place may not work in another. It’s good to have an additional day for testing things out.

Proposed Solution: The young woman working at the Nokia store in Cotonou was very happy to sell us her used old phone for an exorbitant price….. I’m thinking I will go on e-bay or someplace to find some older model phones that work with Frontline SMS to use as a backup. I wonder if there are original (not pirated) phones at local markets….

Weak internet, electricity. Staff and CPS wondered: What if our internet is down, or not strong enough to go into the system and verify the reports in Ushahidi? Will the messages from FrontlineSMS forward to the Ushahidi system if the internet is down? What if there is a power cut? Will FrontlineSMS still capture the SMS’s and forward them?

Proposed Solution: Power and electricity are always a challenge, but we were able with a normal degree of patience to make the system work. I was constantly reminded how my habits are based on having constant electricity and high speed internet. Use patterns are quite different when it’s a weak, intermittent connection, but most people in places with customary weak connections and unreliable electricity have higher tolerances for the situation. Internet and electricity are not really in our hands, but we did use mobile internet as a back up and that worked in some cases. The Ushahidi system will be managed from the two Plan district offices for now, which have good internet (the training site where we were working did not). Eventually if/when the system is passed to local authorities this will need to be looked into.

Our own technical knowledge. We were asked: How can we set it up so that the CPS or Plan staff or local authorities can get an SMS when a case is reported so that they can go immediately to check it out? Can people make reports by email? Can we get statistics on a regular basis from Frontline SMS and Ushahidi to send to our superiors? Is there a way to track the status of each case so that we know where it is in the process from reported to resolved? Well, yes, there is but we couldn’t get the email or the alert system working. Likely this is our lack of experience with the system…. and the weak internet didn’t allow us to do a lot of poking around on user forums while at the workshops to find solutions.

Proposed Solution: We’ll continue to explore FrontlineSMS and Ushahidi to better learn all the functionalities and see what potential ones we can use. We will also add relevant feeds, add an “about” page, clear off the test SMS’s, etc., so that our Ushahidi instance can go live. There are likely add-on functions that we could use to query data in FrontlineSMS for exporting to spreadsheets for sorting and managing (I have done this with Frontline SMS Forms but couldn’t make it work with text message contents). We will look into to a way to manage the status of each incident report, moving from reported into FrontlineSMS, approved in Ushahidi, sent out by alert to the relevant authority for verification, verification completed and marked in the system (hopefully with a report), and some kind of closure of the incident – what response was given or what legal or community resolution process was started and what was the result – and finally, incident closed. Some of the applications developed during Ushahidi Haiti may be useful for us here, or those being used by FrontlineSMS: Medic.

Privacy and protection for violence victims/witnesses who report. In this sense we have two challenges. Can we capture all the information that comes in, yet scrub it before publication on Ushahidi so that it doesn’t identify the victim or alleged perpetrators, yet keep it in a file for the local authorities to follow up and respond? And a second challenge: If everyone knows everything that happens in the community, how can we ensure privacy and confidentiality for those who report?

Proposed Solution: Find out how this was managed in the Haiti situation in the case of names of missing or separated children. Learn more about all of the possible data exports from both FrontlineSMS and Ushahidi. Find out if a separate box for “Private Information” could be added to the report section of Ushahidi for information to be kept in the system but not published on the public site itself or if there is a program that can query the data base either in FrontlineSMS or Ushahidi. The second challenge, that of information confidentiality at the community level, is actually more of a concern. Staff will have follow up meetings with children and youth to identify additional ways to ensure confidentiality at the community level.

What if your phone rings while you are making a video report with it!? Strangely enough, this was one of the hottest questions with the most debate at the workshop. I found that amusing, but it was a question that needed to be resolved then and there. I suggested that it was unprofessional/rude to answer your phone if you were in the middle of a video testimony. But what if your family has been in an accident?! What if it’s an emergency!?

Proposed Solution: OK, well in the end we decided it was up to each individual to decide what to do!

Next steps.

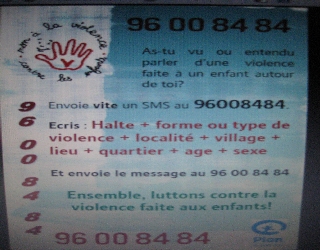

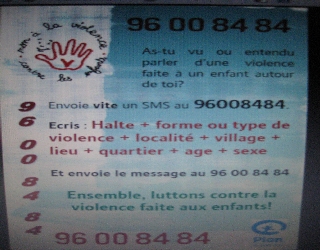

Draft poster. Information to send in the SMS will be altered to reflect input from the CPS.

Our main next steps will be follow up training for Plan staff, Ministry of the Family and Center for Social Protection, including discussions on how to pass management of the system over to them. We’ll also continue to support youth to promote the SMS hotline and to do their video and photo testimonies. We will continuously monitor how the system is working and in about 6-12 months we’ll evaluate what has happened thus far with the system in order to make decisions about potential scaling up to the national level in Benin and/or to other countries. And we’ll follow up on resolving any of the challenges noted above. During the pilot phase we will also tweak the system according to suggestions by users – including the youth, the CPS, Plan staff, and other reporters and responders. For the evaluation, we will want to measure results and factor in a variety of elements that may impact on them, both those related to ICTs and those not related to ICTs.

Key principles confirmed.

Your ICT system needs to rest on an existing information and communications flow. Conversations about a new ICT system can be a catalyst to help identify and map out or even adjust that flow, but it’s critical to understand how information flows currently, and to find points where ICT systems can help to improve the flow.

End user input and testing is critical. We learned a lot and our thinking evolved exponentially during the workshops because we had children and youth present, as well as Plan frontline staff who work on child protection at the community and district levels, community members, local authorities responsible for child protection and responding to cases of violence, and the relevant ministry. At first, my colleagues from the Country Office and I were uncertain that the system could be used for more than gathering information on violence for future decisions; we didn’t feel confident that there was a reliable local/national response system in place. We wondered what the point of collecting information was if there would be nothing done about it.

However, the excitement of the CPS, children, and Plan staff working at the district level changed our thinking, and during the workshop we adapted it towards supplying information for future decisions as well as for immediate response. Local authorities did have concerns about their own capacity to respond, but embraced the system and its potential to help them do their jobs. They suggested many ways to improve it, and fleshed out our original ideas on how the information should flow to those responsible for responding and supporting victims, including local actors that we hadn’t thought of during the initial design phase.

The CPS, for example, suggested that the SMS’s should contain the full name of the victim, which is something we hadn’t thought was necessary for information gathering. “We will have a much easier time finding the victim and responding if we have a first and last name.”

Testing SMS with the youth was important. We initially set up the word “HALTE” as our key word, but during testing noticed that people were spelling it “HALT” and “ALT” in their messages. So we adjusted the key word in FrontlineSMS to “ALT” to capture the alternative spellings that people might use when sending in reports. Something we can find out during the next 6 month testing period is how to set up the system for local languages as well. Local staff brought up the issue of adult literacy. During local promotion of the violence prevention hotline these will all be key factors to consider.

Youth's role in promoting the line and orienting their peers will be critical.

The role of the participating youth leaders was a bit nebulous before the workshops for me. I wasn’t clear if they were to be those who reported violence or if they would have another role. I was concerned about potential retaliation against them if they played a leading role in reporting violence. At the workshops it became very clear what they saw as their role – working to promote the SMS number for violence reporting, taking testimonials from youth and community members on the situation of violence, carrying out radio and poster campaigns against violence, leading educational sessions at schools and in their communities about violence and the SMS line, working to approach local leaders and decision makers to engage them in the campaign, and orienting those who had questions about which authorities and institutions they could approach for support if they had been victims of violence. They are also key people to consult with around how the system is working during the monitoring and evaluation – what are the challenges children and youth face in reporting by SMS, how can we work around them, what other factors do we need to consider.

Input from the CPS and Ministry was critical to flesh out the information flow. Participation by the CPS and Plan’s Child Protection point persons who know how things work on the ground brought us amazing knowledge on who should be involved and who should receive reports and alerts, and at what levels different parts of the system should be managed. Their involvement from the start was key for making the system function now, for sustainability over time, and for potentially scaling to a national-level system.

Continued monitoring and evaluation of the effort will be critical for learning and potential scaling to a national system in Benin and for sharing with other countries or for other similar initiatives. We’ll establish indicators for the various steps/aspects outlined in the information flow diagram. As we pilot the system in these 2 districts in Benin, we will also want to pay close attention to things like: additional costs to maintain the system; reporting and response rates; legal action in severe cases; adoption of the system and its sustained use by local entities/government bodies (Ministry of the Family and Center for Social Protection); suggestions from users on how to improve the system; privacy breaches at community level and any consequences; numbers of verified cases; number of actual prosecution or action taken once cases are reported and verified; quality of local level promotion of the hotline and education to users on how to report; progress in obtaining the green (free text) line; factors deterring people at different levels from using the system.

The end goal, something to evaluate in the long term, is whether actual levels of violence and abuse go down over time, and what role this system had in that. Our main assumption — that education, awareness, reporting and response, and follow up action actually make a difference in reducing violence — needs also to be confirmed.

Related posts on Wait… What?

If you are still in the mood to read… I added a 7a and a 7b to my 7 or more questions to ask before adding ICTs post based on suggestions from readers and my time in Benin.

Here is an update on the project after 2 months: Tweaking: SMS violence reporting system in Benin

For background on the broader Violence against Children (VAC) initiative:

Fostering a new political consciousness on violence against children

Breaking it Down: Violence against Children

Read Full Post »