This is a guest post by Roland Berehoudougou, disaster risk manager for Plan International’s West Africa Region. He explains the numerous factors that came together and conspired against the people of the Sahel, transforming the lean season into an emergency.

Photo: Roland Berehoudougou.

When Plan International and other aid agencies sounded the alarm bells and appealed for public assistance to finance an emergency response to the Sahel Food Crisis, there were those sceptics who saw this crisis as an annual chronic food shortage which was being exploited by aid agencies to raise money.

Those skeptics were wrong.

So what is an emergency? What is a food crisis? What is involved in declaring an emergency or pronouncing a situation to be a “food crisis”? A number of issues are taken into consideration including forecast about the availability, cost of food, environmental factors and other internal and external factors which are discussed below.

The Sahel Food Crisis is the result of a complex emergency in which these factors have come together to create this food and nutritional crisis. In fact, had these not occurred then there would be no food crisis, no emergency, and no fundraising appeals.

Drought causes conflict

In the last three to five years, the people in the Sahel have been confronted with either lower than average rain, normal rainfall or excessive rainfall causing floods. As a result harvest levels have been good in some places and poor in others.

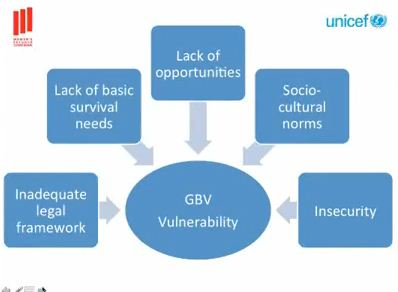

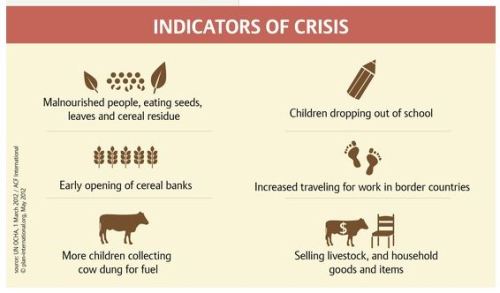

In countries of poor harvests, farmers and their families have been coping using straightforward approaches of cutting back on their expenses. In the Sahel, families sold their livestock; others sold their furniture and other possessions. After three consecutive years, their assets have been depleted and men, women and children have been looking for work to supplement household incomes.

The conflicts in Cote d’Ivoire, the Maghreb, and Libya meant that more than 200,000 migrant workers from the Sahel had to flee those countries and return home. Given the average size of families in the Sahel, about 7-12 members per family, two million people suddenly became affected and had reduced incomes.

In addition, the Malian refugees which poured over the borders into neighbouring countries are an additional stress on food insecure areas. For every one refugee, there are five animals. So if you consider 375,000 animals coming over with 75,000 refugees, for example, those animals can dry up a water-scarce irrigation dam in just few days. Yet, cattle are a lifeline and in a food crisis, they cannot be forgotten.

In addition to depriving people of a considerable source of income, the drought in the Sahel is a source of conflict. Shepherds, for example, who are forced to take their animals southward in search of pasture, come into conflict with farmers.

Cultural differences

People in the Sahel eat a different staple to what is grown outside the region and this has implications during a food crisis. Let’s take a scenario where countries on the west coast, such as Liberia or Cote d’Ivoire, may have enough food to export. However, it is not the type of food that people in the Sahel eat and they therefore won’t import it. Instead they import from one another at prevailing market rates which has a knock-on effect on availability and cost.

Market forces – influenced by global factors – dictate price. There is a common market across West Africa where traders move and sell freely. When Nigeria is buying, WFP is buying, other NGOs are buying the price increases. If you look at food prices you will see that prices this year compared to the same period last year is more than 100% in Mali, more than 70% in Burkina 42% in Niger.

So, as an NGO, Plan International had to change its strategy and approach our donors for permission to do cash-for-work or food-for-work programmes rather than waiting to do food distribution programmes after the food stock is totally depleted.

A food crisis may, therefore, not necessarily mean a shortage of food but rather the inability of a people to afford to buy the food.

Arab Spring

In addition to the complications of prolonged inconsistent harvest levels, market forces, and inflow of refugees and their livestock, the situation has become complicated by the rise of desert locusts this year.

The breeding grounds of locusts are in the border areas of Libya and Algeria. When the Gadaffi government was in office, they provided a lot of money for insect control in locust breeding grounds but since the Arab Spring and events following it the finance for the pest control has dried up. The continuing insecurity on these borders also prevents pest control activities. We are now seeing a different impact of the Arab Spring spilling into the Sahel in the form of locust swarms.

The UN Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) which monitors locust movement say that swarms have been sighted in northern Niger. If these swarms come southward through the agricultural belt farmers will experience yet another problem. When these clouds of locusts descend on newly planted fields, they can devour acres of crops and trees in just 30 minutes. The locust swarms have also been sighted in northern Mali but because of the insecurity, no one can go there to control the pests.

NGOs do not do pest control as it is a very costly exercise involving planes and other equipment which we do not have. This role falls to specialised agencies such as FAO and governments. This is a looming disaster.

Road to hell

To cope with the food crisis, children have left school and have taken to the road to find work to help their parents. Some girls are working as domestic help in homes, other are begging on the streets, and boys are finding work in traditional gold mining in Burkina and Niger. A number of serious hazards face these children including respiratory problems from inhalation of dust and exposure to mercury, arsenic and other chemicals used in the process.

Many children who go to work on plantations, in cotton fields and other types of farming also face risks of exploitation and potential trafficking.

Finding solutions

At Plan we are trying to address the food insecurity, in the areas we work, in a holistic way.

We are providing drought-resistant seeds, supporting the government to train farmers in drought-season activities and supporting the 3N programme (“Niger Nourish Nigeriens”). One of its principal objectives is reducing dependence on climate through irrigation and rain water collection projects.

Plan, whose core work is Child Centred Community Development (CCCD), is also empowering communities to get involved in the cereal market and beat speculators at their own game by creating community-managed cereal banks. After a harvest the price of cereal drops and farmers are forced to sell their crops at low prices to meet the schooling cost for their children and other social costs. Speculators buy the cereal and store it until food shortages kick-in around mid-year and then release the cereal at high market prices.

Plan-supported communities are doing the same thing – except that they sell at a lower price to members of their village. The income generated is used to increase the storage capacity of the cereal bank and support social infrastructures in the village such as building facilities like medical centres and schools.

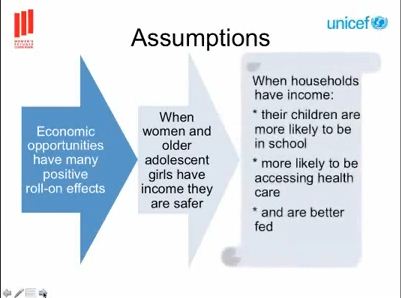

We are also implementing micro-finance project for women and youth using the VSLA strategy (www.vsla.net). We have discovered that if we provide economic empowerment for women then there is a trickle down effecting benefiting children who will receive balance meals, medical care and an education. We are seeing improvements in the quality of life for families in our programme areas.

Using this approach, many villages are now being lifted out of poverty and Plan is replicating this in other areas in which we are working.

No handouts

When Plan appealed to developing nations for assistance for the Sahel Food Crisis, it was not to address an annual chronic food shortage. It was to address a complex emergency that has stretched an already stressed situation to its breaking point which in turn has put four million children at risk of malnutrition.

No one is ever happy about being in a situation to ask for help to feed their families.

Plan is using aid money in such a way so as to prevent dependency on long-term aid. The United Nations agencies of OCHA and UNDP have demonstrated that for a dollar of foreign aid spent on preventing disasters saves an average of seven dollars in humanitarian disaster response.

At Plan we are seeking to empower and support the people living the Sahel to get out of the situation themselves. We are in it for the long haul. We are working hard to make ourselves and our work redundant and build resilience in the Sahel and hope. None of this is possible without the support of governments and people from the rest of the world.

Read Full Post »