There is a lot of talk about “Child Protection” these days and an increased awareness of the vulnerability of children who are separated from their parents or who have lost them due to the Haiti earthquake But what exactly does “Child Protection” mean? What does a child protection system look like on the ground? How can child protection mechanisms be set up during an emergency phase, and how can they be turned into a sustainable mechanism post-crisis?

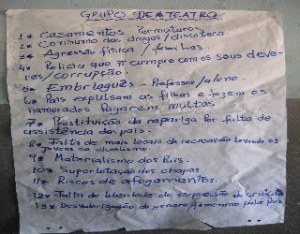

Jose Francisco de Sousa (“Quico”), a co-worker of mine at Plan Timor-Leste, sent me written information on Plan’s child protection work in the 2006 crisis response there and talked me through some of details below. Photo: Quico.

Jose Francisco de Sousa (“Quico”), a co-worker of mine at Plan Timor-Leste, sent me written information on Plan’s child protection work in the 2006 crisis response there and talked me through some of details below. Photo: Quico.

Plan was active in the broader emergency response in Timor-Leste following the political crisis of April 2006 through work in over 40 camps for Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs). (For some deeper insight into Timor-Leste, check out this post by my twitter pal @giantpandinha).

In Timor-Leste, Plan was one of the first agencies to respond as Site Liaison Support (SLS), responsible for the coordination, operation and management of camp activities within days of the crisis. Plan’s specific focus was on addressing the needs of children in the camps, covering service provision such as the delivery of potable water to 15,000 IDPs, addressing hygiene and sanitation issues to improve health, and training youth in conflict resolution skills to aid the nation’s peace building process, and child protection.

Plan’s child protection approach included identifying, monitoring and protecting children at risk, setting up referral systems, training communities in child rights and child protection strategies and mechanisms, and ‘seconding’ Quico as an advisor to the government to strengthen its child protection systems.

Quico was “loaned out” to the Ministry of Social Solidarity (MSS) to build upon existing capacities in the Ministry of Social Solidarity (Child Protection Department) and to ensure a strongly coordinated sectoral, systems-building approach to the child protection response. Through this process, the government came to see child protection as a priority in the long term and eventually established a Child Protection Department under the MSS. So, in other words, the emergency child protection mechanisms established during the crisis were successfully built into a sustainable child protection system in the long term, and services are now available in the district and sub-district levels across the country.

“When the crisis began in Timor Leste, it was very difficult for us to get any resources on how best we could assist internally displaced people. During the emergency, there were many NGOs and other organizations trying to support the internally displaced through different approaches. The focus was mainly to provide the basic needs. There was no proper coordination strategy/mechanism that included broader child protection issues.

I would say that if we look at the nature of the disasters in Timor-Leste and what is happening in Haiti right now, It’s different, but I imagine (correct me if I’m wrong) that the impact of the disasters might be same, where instability is created in different sectors leading to broader child protection issues.

Plan responded to the emergency in Dili (the Capital of Timor-Leste) with immediate practical child protection measures focusing on the prevention of family separation, and the promotion of safety, and health and hygiene in camps. We also prioritised co-ordination of child protection actors by initiating a Child Protection Working Group. This filled a leadership vacuum whilst building the capacity of the Government to gradually take over leadership responsibility.”

Keep reading for an overview of the Toolkit…..or download it here.

————————————————–

Plan Timor-Leste’s Child Protection Emergency Toolkit is divided into 7 parts:

1. Overview of Framework & Standards Related to an Emergency Response in Timor-Leste

This section aims to give an overview of the international, national and organizational laws, policies, standards and approaches to child protection in emergencies in order have clear guidance on how to create an appropriate framework for a potential response that is in line with global, national and internal organizational laws and policies on Child Protection in Emergencies. (If replicating the toolkit, these documents would need to be adapted to the country context). Users of the toolkit should read this section before they go on to use the other sections in the toolkit. These overviews are important to integrate into Child Protection in Emergency trainings and orientation for new staff recruited in the event of an emergency.

Some of the legal instruments and Humanitarian Principles Applicable to Child Protection in Emergencies in Timor-Leste included:

- Overview of Approaches and Guidelines in Child Protection in Emergency

- Timor-Leste Structural Framework of the Current System for Child Protection

- Timor-Leste Legal Framework for Child Protection

- Plan’s Approach to Emergency

- Summary of Learning and Recommendations from 2006 Emergency Child Protection Response

2. Emergency preparedness

The section includes an overview of steps that should be taken to ensure that Plan offices are prepared for an emergency. It’s divided into two areas – programmatic preparedness and administrative preparedness. It also includes the practical internal financial codes for general emergency preparedness activities so that these are compiled and readily available to support and inform activities and rapid proposal writing in the event of an emergency. These are also useful for Country Offices to be prepared for emergency in the long term.

Programmatically, the tools include government and Child Protection Working Group contingency planning, risk analysis and scenario planning, child protection activity mapping and definition of roles and responsibilities. They also include tools developed specifically for the geographical areas where a child protection response might potentially be needed, such as contact lists for child protection actors at the municipal level, and community-based hazard, risk and capacity maps developed by children and their communities as part of Plan’s on-going mitigation activities.

The administrative tools cover generic job responsibilities, a general child protection in emergencies orientation session for newly recruited staff or those who are new to emergency response. The human resource structure of a response is defined and responsibilities are allocated within the current staff organigram. Advocacy and media standards and a stock list of necessary items for the first phase of an emergency response are also included.

3. Initial emergency response

This section contains the basic tools relevant to an initial emergency response. The emergency planning tools included in the previous section are also relevant to ensuring the most efficient response possible, in line with Plan’s community-based approach. The shape of the response will depend largely on the type, scale and location of the emergency, and any tools need to be adapted according to this context.

“One of the tools here is a child protection message to Camp Managers. During the emergency period, Plan was assigned to be responsible for a certain number of IDPs. One of our focuses was to establish and ensure that the structure in the IDP was functioning to assist the IDP’s and that we established the camp. But we also wanted to make sure that child protection was understood and prioritized in displaced persons camps. This meant that we discussed children and child centered programming with camp managers, and they worked to ensure that there would be no discrimination towards children and their families during the emergency.”

This was difficult for us to introduce in the beginning of the crisis, as people tended to have different thoughts and priorities, and it gave additional works to the IDPs. In addition to that, some organizations did not have a mandate for “child centeredness.” So we started facilitating child protection focused workshops for camp managers and other NGOs, and getting their commitment to be involved in process. Aside from that we also guided the camp manager on using the checklists as well as we assigned Plan, government and other NGO staff (who were also in IDPs) to support throughout the process, and it worked.

One of the problems that we encountered was related to volunteers. Since we were establishing a new system, we needed people to take responsibility at different levels. Camp managers already had additional child protection tasks for the whole camp, so they were supported by child protection focal points and child protection teams in each block of IDPs. I wouldn’t say it all worked perfectly. There were issues among volunteers that were brought to the Child Protection Working Group to discuss. Some NGOs who were also assigned in the IDP camps had a policy of paying camp managers and teams, which created jealously and conflict between them and the volunteers. But in the end, we developed guidelines for volunteers, establishing from the start that we would not give them cash but rather give them recognition and reward such as:

· identification cards recognizing them as volunteers

· training and continuing refresher courses

· certificates for every completed training course

· promotional t-shirts, hats, umbrellas & bags, whenever available

· public acknowledgment

· certificate of community service for every 3 months of services rendered

· access to information about suitable job vacancies in NGOs”

4. Child protection assessment

This section contains tools for use in assessing child protection-related needs. It draws heavily from the Inter Agency First Phase Child Protection Resource Kit developed by the IASC Child Protection Working Group. The assessment contains generic questions relevant to a range of child protection issues common to emergencies. They are adapted and modified according to the context of the emergency and the child protection issues that are identified as emerging. Training on ethical considerations and assessment methodologies should be conducted as necessary.

“There are 8 main focus questions in the Questionnaire for Children, for example. To find out about children’s psycho-social well being, we ask the questions:

· What are the things/activities that you like the most?

· What kind of things makes you happy or comfortable?

· What are the things/activities that you dislike?

· What kind of things makes you angry or sad?

· What kind of activities would you like to have here?

· What are the main problems that you face now?

· What would help you solve these problems?

· What are your biggest concerns or worries about the future? What do you think would help?

· Which people make you happy in the community? Why?

· Which people make you unhappy in the community? Why?”

5. Building a Child Protection System in an Emergency

The section looks first at developing child protection systems in the context of displacement. It then looks at supporting district, sub-district and village child protection systems to respond to the needs of displaced people living in host communities and other disaster-affected communities. It goes on to look at the implementation of the Child Protection Policy and ensuring the effective management of individual child protection cases. This sub-section contains guidelines on monitoring and reporting grave violations of children’s rights.

6. Key issues for children in emergency

This section looks at some of the issues that children commonly face in emergencies and appropriate child protection responses in line with international standards and according to Plan’s mandate and experience. The three key issues covered in detail are: Family Separation, Sexual Violence against Children, Psychosocial Support for Children. Each of these three issues has a sub-section containing a summary of standards and guidelines, process for prevention and response, necessary tools, and a training module for staff.

7. Monitoring and Evaluation

This section contains the tools used to monitor and evaluate child protection in emergencies interventions. These are based on tools already used by the Plan Timor-Leste Office. They are adjusted according to the needs of an emergency context and are supplemented with additional tools in line with good practice.

“In Haiti, I would say that children separated from their parents will need to be especially considered, while people will also need to be alert for the effects that the crisis may have, for example, increased violence. This will be a special concern if there were any political issues before the crisis. Psychosocial activities are very, very important too, the other key areas are likely to be water and sanitation, heath problems and education. Coordination mechanisms between aid organizations must be considered, as each organization will have their own approach but in this situation each organization needs to think about the wellbeing of children and the community.”

More resources:

—————

Related posts on Wait… What?:

Read Full Post »

Jose Francisco de Sousa (“Quico”), a co-worker of mine at Plan Timor-Leste, sent me written information on Plan’s child protection work in the 2006 crisis response there and talked me through some of details below. Photo: Quico.

Jose Francisco de Sousa (“Quico”), a co-worker of mine at Plan Timor-Leste, sent me written information on Plan’s child protection work in the 2006 crisis response there and talked me through some of details below. Photo: Quico.