Yesterday I inadvertently clicked on a link to the first blog post by Talesfromthehood that I think I ever read. The post starts by saying ‘There is just no way around the critique that aid is ultimately about imposing change from outside….you’ve got to make your peace with that reality.’ (Not what I like to hear). Tales goes on to say that we need to better define the term ‘bottom up‘ development and concludes that we may really not be talking about ‘bottom up‘ development at all, but more about ‘meeting in the middle‘.

The idea of imposing change from the outside is a little uncomfortable sounding when you normally think of your work as ‘bottom up‘, and you have seen the countless problems that ‘top down‘ approaches create. But funny that Tales happened to include a link to that particular post in the more recent post that I was reading, because I was in the process of writing up some notes about a community development approach that I believe is quite good. And looking more closely, it actually sounds a lot more like ‘meeting in the middle‘ than ‘bottom up‘….

I spent this past week in a workshop with colleagues from Cameroon, Mozambique and Kenya discussing a program we’re all working on at different levels. The initiative (Youth Empowerment through Technology, Arts and Media -YETAM) aims to build skills in youth from rural areas to claim space at community, district, national and global levels to bring forth their agendas. It looks to create an environment where peers, adults, decision makers, partners, schools, and our own organization are more open and supportive to young people’s participation and ideas. It uses arts and ICTs (both new and traditional ones) as tools for youth to examine their lives and their communities; identify assets, strengths and challenges; build skills; share their agendas; and lead actions to bring about long term and positive change.

It is clear from listening to my colleagues that ICTs in this case have been effective catalysts, tools and motivators for youth participation and voice in their communities and beyond, but that other elements were just as critical to the program’s successes. Throughout the meeting they kept saying things like ‘we are adopting the YETAM approach for our disaster risk reduction work’ or ‘we are incorporating the YETAM approach into our strategic plans’ and ‘we are going to use the YETAM approach with new communities’. So I asked them if they could put into words exactly what they considered ‘the YETAM approach‘ to be so that we could document it.

I furiously typed away as they discussed how they are working, and what they consider to be the elements and benefits of the ‘YETAM approach.’ And it’s probably a pretty good example of what is normally called a ‘bottom up approach‘ but which might actually be a ‘meeting in the middle approach.’ And I’m definitely OK with that.

I like the approach because it builds on good community development practices that we’ve endorsed as an organization for quite awhile. It brings in new ideas, new tools and new ways of thinking about things at the community level, but it doesn’t do so in a top-down way. It doesn’t encourage youth to abruptly raise controversial issues and then leave them to deal with the consequences. It thinks about implications of actions and ownership. It addresses the ‘what’s in it for me?’ questions but doesn’t turn the answer into unsustainable handouts. It looks to instill a sense of accountability across the board. On top of all that, it incorporates ICT tools in an integrated way that gets youth excited about engaging and participating and helps them take a lead role in advocating for themselves.

YETAM Point Persons: Mballa (Cameroon partner), Anthony (Plan Kenya), Pedro (Plan Mozambique), Lauren (Mozambique Peace Corps Volunteer teacher), Nordino (Plan Mozambique) and Judith (Plan Cameroon)

So, ‘bottom up’, or ‘meeting in the middle’ or whatever, here’s ‘the YETAM approach’:

Meetings…. Lots of them. We meet with men, with women, with children, with youth, with local authorities and district officials and relevant ministries, with partner organizations and community based organization, in short, with all those who have a stake in the initiative, to get their input. This is an opportunity to understand what everyone wants to get out of the project, what value it adds to what they are doing or what they aspire to do, and what role everyone will play. Then we meet with everyone all together at a community assembly. Once we pull together what everyone’s interests and contributions are, we can go forward. This means a lot of time and a lot of meetings, which can be tiresome, but in the end it is worth doing for the long term success of the initiative.

Partnerships. Everyone brings something to the table – communities, local partners, young people, schools, teachers, local leaders, and us. So we work to ensure that the contributions of each entity are clear and detailed, and that all sides are accountable if they don’t hold up their end of the deal. The community might contribute time or food or labor or a training space or some other resources that they have. We might contribute funds or technical advice or facilitators or the like. Local partners might bring in technical expertise; schools or governments something else. Youth are putting in time and efforts also. To ensure that the project holds up and succeeds, we negotiate with all involved partners to see what they can contribute. If you see that people are not willing to put something into the initiative, it means that it is not of value to them. If you push the project on people, and move it forward without it having value for them, it will be a constant struggle and a headache. Seeing the level of commitment and interest in different community members can tell you if the initiative is a good thing for the community or not, so that you can adjust it and be sure it’s worth doing, not pursue it, or continue to work on buy in if some parts of the community are interested, but others are not.

Accountability. We set up agreements with all partners in the initiative, detailing what everyone will contribute and what they will get out of it, establishing everyone’s roles. This is critical for accountability on all sides, and gives everyone involved a common basis for any future discussions or disputes, including if the community wants to hold us or a local partner accountable for not fulfilling our promises.

Buy-in. We don’t pay people to participate in projects or for sitting in workshops. If you pay people to participate in a project once, you will have to pay them forever and it becomes a weak project without any real buy-in. Our particular role in community development is not creating short term jobs, but contributing to long term sustainable improvements. So what we do is to sit with the community and any participating partners or individuals from the very beginning and fully discuss the project with them. Then those who participate do so with a clear understanding of the set up, the longer term goals, the value to the community, and they have decided whether they want to be involved, and what is their level of commitment.

Some NGOs find that paying people to participate is an easy way to move budgets. This may help get things done in the short term, but for the type of programming that we do, it doesn’t work in the long term. It takes away people’s ownership of their community’s development if you pay them a fee to participate in their own project. So to avoid misunderstandings, everything needs to be clear before the project activities even start. We spend time with the community and all those who would be involved. In the very first meetings with the community before concrete activities even get started, we address the issue of payment. It’s not our project for the community and they are not working for us – it’s the community’s project. We do negotiate with them to cover additional expenses that they may incur for participation in a workshop or event, for example, transport, food, etc.

What’s in it for me? Many NGOs have come around before, just giving hand outs, and people are used to seeing an NGO come in paternalistically to give them things. They imagine that you have a lot of money and you’ll arrive to just start handing things out. This is not how we want to work. But people want to know – well, I’m not making any money from this, and I’m going above and beyond, so what do I personally get out of it? What’s in it for me? They even ask this directly, and that is normal. There’s a need to help people think beyond the immediate project. What value does this project add to people’s lives in the long term, to what they do on a daily basis? If they are not thinking in the long-term, it may be hard for them to see value in the project. If during this discussion with them it’s clear that people don’t see any value in an initiative, then you should be aware that they are not really going to participate. And that is also logical – if there’s really nothing in it for them, why should they do it? So you need to listen to people and be prepared to discuss and redesign and renegotiate the project so that they are really getting something of value for themselves and the community out of it. If you come in with an idea from the outside and people don’t see value for themselves, and you go the easy route and pay people to participate in the project, you will see the whole thing fall apart and the efforts will have been for nothing, you will see no impact. So we take the time and discuss and co-design with the community to make it all work. That way it becomes a catalyst for long term positive changes.

Understanding local culture and how your government works. We work to involve local governments and ministries in this work as well as other kinds of decision makers. It’s important to understand how local culture works and what the hierarchies and protocols are in order to do this successfully. It’s critical to know what your government is like and how they work. If you are not aware of this, it will create problems. You need to know how to engage teachers, district officials, school directors. We follow local protocols so that we can ensure good participation and involvement, especially when we need support from the government or ministries in order to move forward with something. We involve people at these levels also because they are the duty bearers who have the ultimate responsibility here in our countries. If you leave them out of the equation, you are really harming the initiative and its sustainability as well as losing out on an opportunity to make sustainable changes happen at that higher level.

Respecting community schedules. Communities are not sitting around, waiting for NGOs to show up so that they can participate in NGO activities and projects. They have their own lives, their own other projects, their own work and their own goals that we need to harmonize with. Projects that we are supporting are just one part of what community members are doing in their lives. So we need to be flexible and let the community dictate the pace. Sometimes partners, colleagues from other parts of the organization and outside donors do not understand this, which can cause conflicts and misunderstandings with the community. In our case, for example, we are working with youth. They are in school. We can’t interrupt their primary responsibility, which is getting their education, so we work with them during school holidays or after school. Often parents want them to work during their school holidays. So again those meetings with parents, community leaders and so on become very important so that they see that their children are participating in a broader initiative and they see the value in it.

Gradual processes. In this particular project, we are working with youth to have more of a voice. This can be threatening to some adults in the community, and can go against local norms and culture, just like working with women to overcome gender discrimination can. If youth are not used to voicing their opinions, they may be fearful of reprisals. We don’t want to show up, give young people the tools and means to speak out, create conflict in the community, and leave. This can be very counterproductive and even dangerous. This is where those meetings and building those relationships with different parts of the community again become very critical. We’ve adapted a methodology of intergenerational dialogue. We sit with the elders, with the community leaders who hold elective positions, and share the project idea and what might come out of it, sit with women, sit with youth. This is like a focus group. You don’t go in accusing people either. You ask them – what issues do you think youth are facing in the community? They will tell you, and when you’ve heard from everyone, you triangulate the information. Then you find a way to bring everyone together to find common points to start from. The shift cannot come so strong and fast. You need to take a slow process.

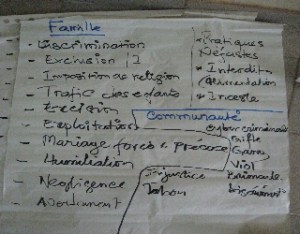

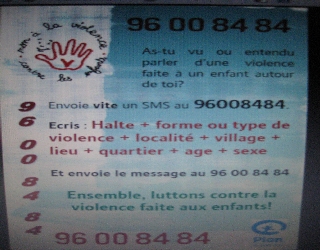

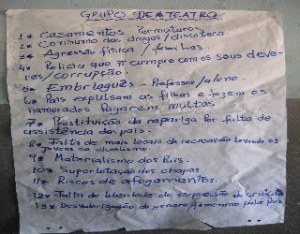

Listening to children and youth. The strongest point of reference will be what children and youth have talked about, because that is our focus. And for a child to tell you something, it’s taken a lot of work inside themselves to say something. We had one case where a child decided to stand up and raise the issue of incest at an inter-generational dialogue meeting. A man stood up and said ‘you are lying, this doesn’t happen here’. But there had been an on-going community process already, and there were other people in the community who were aware and were prepared to stand up and support the child. In that case, a man stood behind the boy and said, ‘in our community we don’t talk about this, and it takes courage. Let’s listen to the boy.’ This community process and work is really important to give confidence to the children to be able to speak. If you are not yet at the point where children can stand up publicly and speak out, then ICTs can also be a good tool. We’ve found that children’s radio is an excellent place to speak out anonymously about a sensitive community issue. Children can call in to raise an issue and others can call in to confirm it if it’s happening in the community. Theater, cartooning and other media area also good ways to raise issues. Making a drama video on a sensitive topic and sharing it with the community can also be a way to raise an issue without directly accusing someone or implicating a child or youth for having raised it.

Expecting yourself to be held to task too. If there is a track record in the community with children speaking out but nothing happening or changing, then that will deter them from saying anything. So if you want to go down that road, of encouraging children and youth to speak out, you need to be prepared to take it through to the end, to support them. You have to be prepared to really take children and youth voices seriously, to follow things through to the end. This is actually also true if they raise an area where your own organization has failed, that you yourself have not done something that you promised. If we encourage them to use their voices, we have to expect that they will hold us accountable too. We raise funds in the name of these children and communities, so we need to be accountable to them. We need to be open to children, youth and the community also calling us out. And have no doubt that they will. It’s happened before and will happen again. So we encourage them to challenge us as an organization, to be honest and to hold us to task.

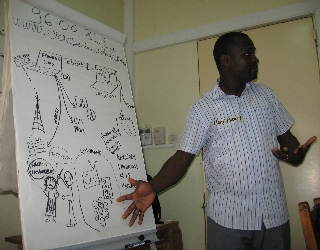

Change and growth from within. As part of the whole community process, we do mapping, problem tree analysis, assets analysis with the youth and accompanying adults, and they learn much more about themselves. They think about where they are coming from and where they are going, and what local resources they have. This offers perpetuity, especially for the children and youth. Because of knowing where you come from, you can know where you are going. Where you dream to be. Using this kind of documentation and these tools actually helps a community to be open to absorbing new things, to be open to change and growth. But not external change and growth, change and growth coming from within the community.

Addressing gender discrimination. As part of the process of mapping and prioritizing issues, there is a lot of discussion. Very often this brings up issues that are closely linked with gender discrimination. We see this over and over again. Because we are working in a safe space and using different tools, the issues come up in a way that is not so threatening. Boys also are at a stage where they are more adaptable. They see their sisters and mothers being victims of discrimination and they are more open to hearing out their female peers. So, we are able then to build a shared agenda that is favorable to girls, and which both boys and girls are then acting on and working to address. Issues like child marriage, early pregnancy, girls’ schooling come up, but there is a way to look at them and do something. We also open opportunities for youth leadership roles within the project, and we’ve seen girls start to fight to have a space there, whereas before they would not have thought that they could play an executive role.

Opening space for youth. We work to build new skills in youth to manage new technology, new media, and to do research in their communities. Through this, youth claim a space that they didn’t have before and can influence certain things, advocate on certain issues they feel are important to them. You see them start taking ownership in communities and in leadership, they want to pick up new things for this role. We used to invite youth to community meetings. We would start with 20 youth, then it would go down to 10, to 4, to 3 to none. They got bored with it because they didn’t see any relation to themselves. But with this integration of technology and arts, youth have a high interest. It’s really bringing in their opinions, their thoughts and ideas to join their voices with their parents. Now they use arts and media to promote communication, dialogue on their issues and look for ways to resolve them. Before they were totally missing. We tried to come in with programs for youth but they never worked before. With this new way of working, they have become more responsible because they are not waiting for adults to come in with something and invite them in to ‘help’. Now they are designing strategies and solutions themselves and bringing these to the table. It’s less easy for politicians and parties to manipulate them and incite them to violence. Arts and media are effective in this way to share ideas, issues and to use in generating dialogue and solutions in their communities.

ICTs providing reach, motivation and skills. In addition to using ICTs to generate interest in young people and for them to take actions in their communities, we also use ICTs as a cost-efficient way of actually advocating at different levels. You can use video at the local level but also at the national, regional and global level. That is cost effective and has a real impact. You can use videos in invited spaces, for example, where governments, schools, other communities, or our organization itself invite children’s and youth’s voices in. But we also support youth to use these tools to claim spaces, to fight for space and to get their voices heard there. We give youth the tools, and you see their brains rewiring. They learn better hand-eye coordination by using a mouse and a computer, and you see then that in class, they can copy from the board without looking at their paper. They learn organizational skills by creating folders and sub folders. They learn structure from filming a video and making a time line while editing it. They learn to speak with adults and decision makers from talking on the radio, using a recorder or a camera. They become more motivated to complete school. All this makes them more effective leaders and advocates for themselves and their agenda. They also know that they’ve learnt a skill that puts them at the top of the pile in their community for jobs now. They are plugged into something that would never have existed for them before.

Related Posts on Wait… What?

7 (or more) questions to ask before adding ICTs

Is this map better than that map?

An example of youth-led community change in Mali